Blog Series on Time

1. Understanding - How Lifestyle Affects Time

Don't rush around trying to meet everybody. Take time for the moment & the people in the here and now...This article will look mainly at the implications of the closeness of a community and the patters of interactions, as a way of understanding how people view time. The frequency of chance face to face encounters is significant.

Don't rush around trying to meet everybody. Take time for the moment & the people in the here and now...This article will look mainly at the implications of the closeness of a community and the patters of interactions, as a way of understanding how people view time. The frequency of chance face to face encounters is significant.

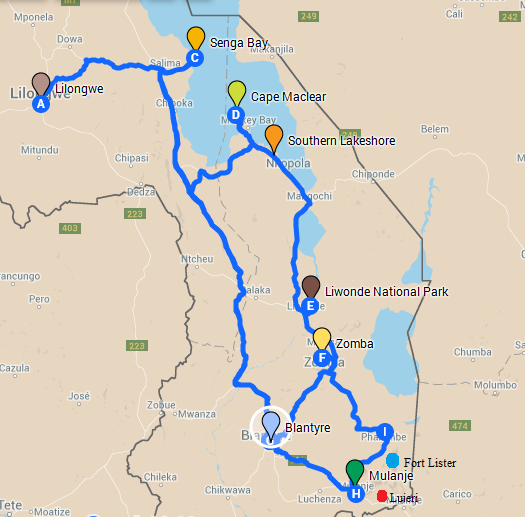

How should someone new to or visiting Malawi cope with some of the differences between life in 'the west' and life in Malawi? Although relevant for visitors and tourists this is perhaps even more important for people who wish to work in Malawi. A lot of westerners who do work in Malawi come here for a short period of time to work on a project...

One difference that is often commented on is time.

My answer to the first question above, the first sentence in this blog post, is that the first thing to do when it comes to handling cultural or societal differences is to understand why there are differences. The reason for this is that if you understand why things are different your attitude is going to be more positive. There is no end of grumpy westerners in Malawi grumbling about things not being how they 'should' be. If you want to be less grumpy than others then the first thing you must address, hopefully before coming to Malawi, is your own mindset.

Aside: on the subject of grumpiness I should point out at this stage that I myself wear a t-shirt with the word 'Crabbit' on it and the Scots dictionary definition of 'Crabbit' is also on the t-shirt. My mother has always said that the t-shirt suits me very well. Due to the imperfection of online dictionary definitions I should perhaps clarify matters by making it quite clear that I am not carnaptious, some people even regard me as a nice person.

Getting back to the main subject. There are many topics that can be written about under 'time', including strategies for making the best use of time in the context of uncertainty, waiting etc. However, to avoid too long a blog post I will try to restrict myself to some thoughts on understanding why there are differences between a western mindset on time and something that is more typically Malawian.

One way to do that is to look at western lifestyles and consider how they has changed over time. One hundred and fifty years ago we all had far fewer aquaintances and far deeper relationships (even friendships) with the smaller number of people who we knew. We also travelled far less and a higher proportion of the population lived in villages than is typical now.

Even in the cities in Malawi many interactions between people are more like they were in the west 150 years ago (e.g. better in some particular ways). I am not talking about some people, I am talking about everyone: rich and poor, Malawian and expat, people with iPhones and people without. The thing is even in the city it does feel a bit like a village. You bump into people you know all the time. Partly that is because a lot of people work in exactly the same place every day and partly because those who do move about move in more particular and predictable routes and patterns than would be the case for the average professional and socialite in cities and towns in the west. One consequence might be that you might have to be slightly more careful about your relationships.

If that is what it is like in the city in Malawi, how much more so in the villages?

What are the practical consequences of that with regard to time? The first thing to say is that if your daily life in the village (in the west, 150 years ago) took you past the butcher, the baker and the candlestick maker you might, as you walk through the village, happen to meet John, or you might not. Instead you might meet Sarah or Geoff and Lesley. As the circle of people who you know is much smaller and you have much more to do with each person you pass it is likely that you will have the necessary 'meeting' with someone you need to see without having the necessity of a useful time / calender / scheduling app on your iPhone. You may well have needed to see 'John' about an important matter but on this occasion he happened not to be behind the counter at the butcher's. Instead Sarah was there and you remember that you had a message to pass on to her from your cousin.

Suddenly spring forward 150 years and imagine yourself in London working as a recruitment consultant. Now, your lifestyle is very different, you live in a big city, you travel a lot and your list of acquaintances and 'contacts' requires an excellent iPhone app where you not only have the person's name, number, email etc etc but also their photo to trigger your memory of which is which. This is also linked to further information on the type of staff / job they are looking for or whether it is the guy you met in the pub on Friday. If you need to meet 'John' at 10.45 am at the Pret or 'Eat.' or whatever other pretentious sounding shop near xyz tube station then you need to be sure that 'John' will be there and then because if not you are not likely to accidently bump into Sarah or Geoff or Lesley. You might happen to see someone you recognise but either a/ you can't quite remember who they are or b/ you wish you hadn't seen them as you never expected to see each other again which was a reasonable hope in a city the size of London.

Now, I hope you can see what I am getting at. But there is another point to follow on logically from this.

If you live in a smaller community where you know most of the people around you and there is a lot less travel than is typical in a modern western city or large town then a number on consequences flow from this, and they can affect how society view's time.

Firstly, there is no absolute need to be sure that John will be standing outside of Embankment tube station at exactly 10.45 am (in the year 2015). If you don't see him when you wander through the village (in the year 1865), you will see him soon enough. Similarly, your time will not be wasted as you are bound to bump into others you need to speak to about something or other, although you cannot be sure who.

This is how I have noticed things in Malawi. Often I have set out at the beginning of the day to achieve xyz, which involves meeting Mr Q. Instead, I have quite unexpectedly achieved abc because Mr Q was nowhere to be seen but instead I happened to meet Mr G who told me about Factor O which I had never considered before. I hope that you can see what I mean.

Something that makes much more sense in a more community type of environment is that you may as well finish off whatever task you are working on, even if it overruns the time that you expected it to take. This is because even if someone was expecting to see you at 2pm they are slightly less likely to have to waste their time if you are delayed. Secondly, if there is already an expectation that time is 'flexible' then people will be more inclined to take that into account when planning what to do while they are waiting for you...

The next consequence of being in a smaller community type of environment is also very important and also profoundly affects time. This factor has to do with the relative importance of relationships when compared with practical tasks.

In Malawi, once you have learned all the various forms of greetings, and experience how long they take, you start to appreciate that there is some sort of difference between time taken for greetings and asking how your family are getting on etc etc. In Malawi it does not really work to say "Let's not stand on ceremony, let's cut to the chase and deal with matters, including some difficult matters, immediately."

It could be argued that it would be fair to say that Malawians spend time prioritising relationships and having time for people rather than strictly limiting time for people in order to spend time on tasks. Malawians for example take a lot of time (and people) for funerals. What I mean is that a lot of people go to funerals. Similarly, those closest to the bereaved will spend the whole night singing hymns and praying with the bereaved. This process and the funeral takes as long as it takes. Assisting the bereaved in their time of mourning and healing takes time. I first really thought about this when my mother talked about how things are in Malawi. She was talking about this in the context of my father's funeral.

So, if the key thing is spending time on people, rather than things or tasks, then the length of time required can be more unpredictable.

Let us compare briefly the length of time it takes to greet people in different languages.

Firstly, English

"Hi"

Secondly, Estonian

"Tere"

For non-Estonian speakers let me translate. 'Tere' means "Hello!!! How are you??? I have not seen you for at least a year. How are your children these days? Wow, they are grown up now. We must go to the sauna next week."

Thirdly, Chichewa

"Ehhhh! Ahhhhh! Mulipo?! Moni mwaswera bwanji achimene wanga? Kunyuma kuli bwino? Ana apita ku sukulu lero? Amai wanu ali bwanji? etc etc"

That means "Hello".

So, what am I saying? I think in summary I mean to say that because circumstances to do with the size and closeness of the community that you are in affects human interactions, including timekeeping arrangements. Different societies and countries operate according to different assumptions and 'social rules' and a large part of that is connected with practical considerations based on the context.

I do not dismiss other considerations with regard to judging how things 'should' be. While there may be good reasons for differences to do with time that is not the end of the story (in my opinion). There are plenty of nuances and variations that make generalising very difficult and dangerous.

For example, my Chichewa teacher was never late for any of the online Skype Chichewa lessons we have run for visitors before they come to Malawi. He himself told me that when dealing with westerners it is very important to adapt to their expectations. Similarly, we hope to ensure that time-keeping for our transfers in Malawi is a top priority.

On another aspect to do with this, just because there are reasons for differences in time that is no full justification for not giving a realistic assessment of how long it is going to take to arrive or do xyz. I don't take the view that every society is perfect according to it's own social rules. On the contrary I think that every human and every society is imperfect. Even if you do not think like that I would think that most of us should be able to agree that different societies or 'cultures' or whatever word you prefer, have different component parts that work in different ways. This is because of the wider context which includes all sorts of practical considerations. These may well not apply in the same way in a different society or practical context.

So, if we can understand why there are differences in different countries, even if we don't fully accept them, then perhaps we can be more 'philosophical' or 'happy' about things. This may be for the best when considering the next issue which could be to do with practical strategies for dealing with cultural differences with regard to time. Another follow up topic to this one may be something that a friend of mine told me about how time is conceptualised differently in Malawi when compared with 'the west'.

O-Sense

O-Sense